Infection with monkeypox: The history, present, and future

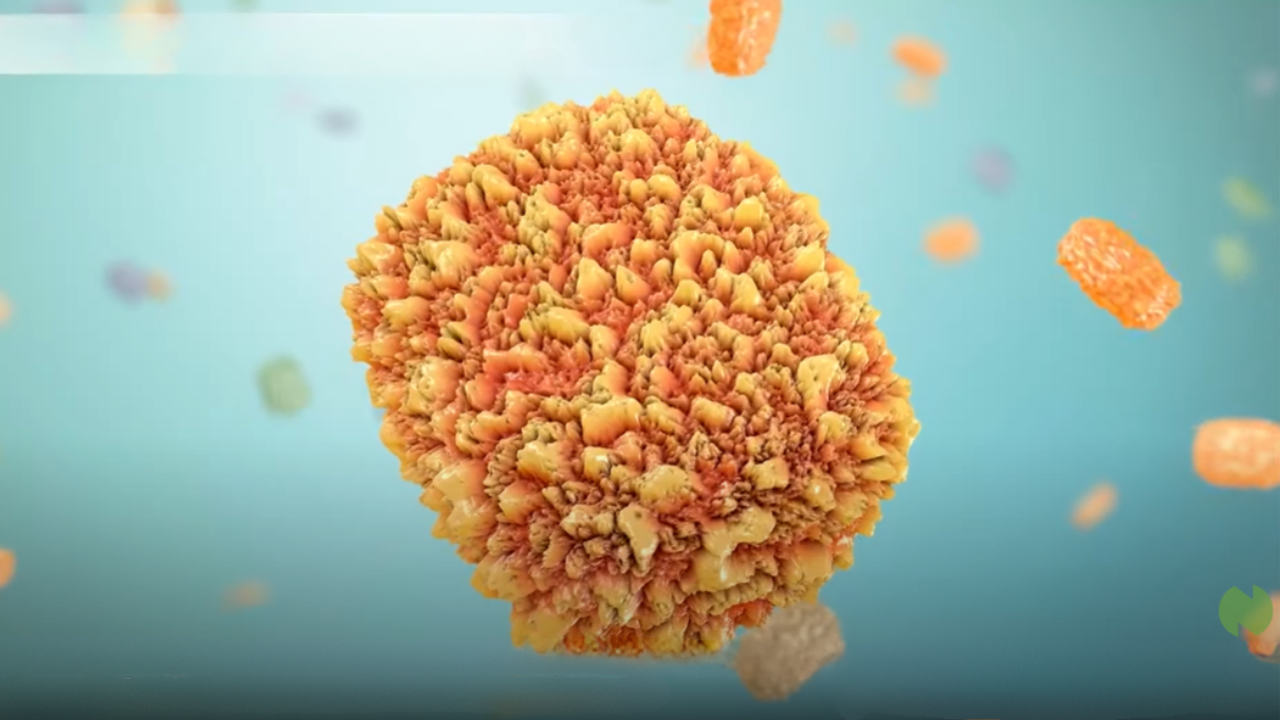

Monkeypox

The orthopoxvirus that produces monkeypox, which is closely linked to the variola virus that causes smallpox, is the cause of this zoonotic infection.

It was termed “monkeypox” because the first case was documented in 1958 among monkeys kept for scientific studies.

In 1971, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reported the first known incidence of monkeypox in humans. However, the first case outside of Africa was identified in the United States in 2003, and it was linked to contact with prairie dogs that were infected as pets. Dormice from West Africa (Ghana) and Gambian stuffed rats were utilized to keep these creatures.

The human monkeypox virus (MPXV), a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Poxviridae family and the orthopoxvirus genus, is one of the four orthopox virus species that may infect people.

The other three, which together create smallpox, which is currently eradicated, are the variola major virus (VARV), cowpox virus, and variola minor virus.

Two genetic clades of the monkeypox virus have been identified: West African and Central African [5]. These two clades differ from one another in terms of epidemiological and clinical characteristics along with geographic variances. The Congo Basin clade, often referred to as the Central African clade, has a case mortality rate (CMR) of roughly 11% with a documented human-to-human transmission, while the West African clade has a CMR of less than 1% with no evidence of human-to-human transmission.

While the symptoms of smallpox and monkeypox are similar, MPX is distinguished from smallpox by the presence of enlarged lymph nodes at the onset of fever. It is unknown how precisely MPXV is communicated to humans.

Primary animal-to-human transmission is thought to occur when people come into contact with infected animals, either directly (by touching, biting, or scratching them) or indirectly (by handling the animals). The precise mechanism(s) of infection are yet to be determined.

It is believed that the virus enters the body by the respiratory system, mucous membranes, or damaged skin (eyes, nose, or mouth) [5]. The signs and symptoms of monkeypox appear 6–13 days apart. Patients with smallpox and monkeypox exhibit comparable clinical manifestations, including identical symptoms and lesions.

Monkeypox frequently has a self-limiting course, despite the fact that it can be severe in certain individuals, such as babies, pregnant women, and those with weakened immune systems.

The world was alerted on May 7, 2022, to the possibility of a monkeypox outbreak in the United Kingdom, following several years in which no cases of the disease had been confirmed in non-endemic countries. Since then, reports of instances have come from Canada and the United States, as well as Sweden and Australia.

As of May 21, 2022, 12 countries where monkeypox is rare had reported 92 confirmed cases (and 28 suspected cases), according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

All infected people up to this point have been identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, and they are all related to the West African clade.

Cases sent from Nigeria to the UK, Israel, and Singapore in 2018 and 2019 have been linked to the monkeypox virus causing the current outbreak.

Since countries are still coping with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is concerning that there might be another outbreak. The truth is that scientists already know a great deal about monkeypox, unlike with COVID-19 in early 2020.

This review aims to raise awareness about potential preventative measures, offer prospective targets for drug discovery and development, and address existing information on monkeypox, including treatment, immunization, and preventive measures.

Using the phrase “monkeypox infection,” a literature search was done on several scientific databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus.

Using MeSH terms related to monkeypox infection, such as antiviral, vaccination, and biomarkers combined with Boolean operators, a total of 1926 publications were located. Out of those, 58 papers addressed the epidemiology, therapy, pathophysiology, and prevention of monkeypox transmission.